Together with our project partners C-EHRN, EHRA, EuroNPUD, the Drug Policy Network South East Europe hosted a Webinar on Decriminalisation of drug use and possession for personal use on 4 December 2025. The aim of the webinar was to present and discuss a policy brief developped in scope of the BOOST project.

The webinar was held in English and Russian. 32 participants from various European countries participated – experts, activists, and policymakers. They demonstrated that the true threat to European safety is not the substances themselves, but a punitive system that costs taxpayers billions, fuels organized crime, and destroys lives.

Marios Atzemis, DPNSEE Board member, presented the policy brief ondecriminalization, highlighting its importance for health, dignity, and human rights, and shared personal experiences on the impact of criminalization.

The fiscal and moral bankruptcy of criminalization

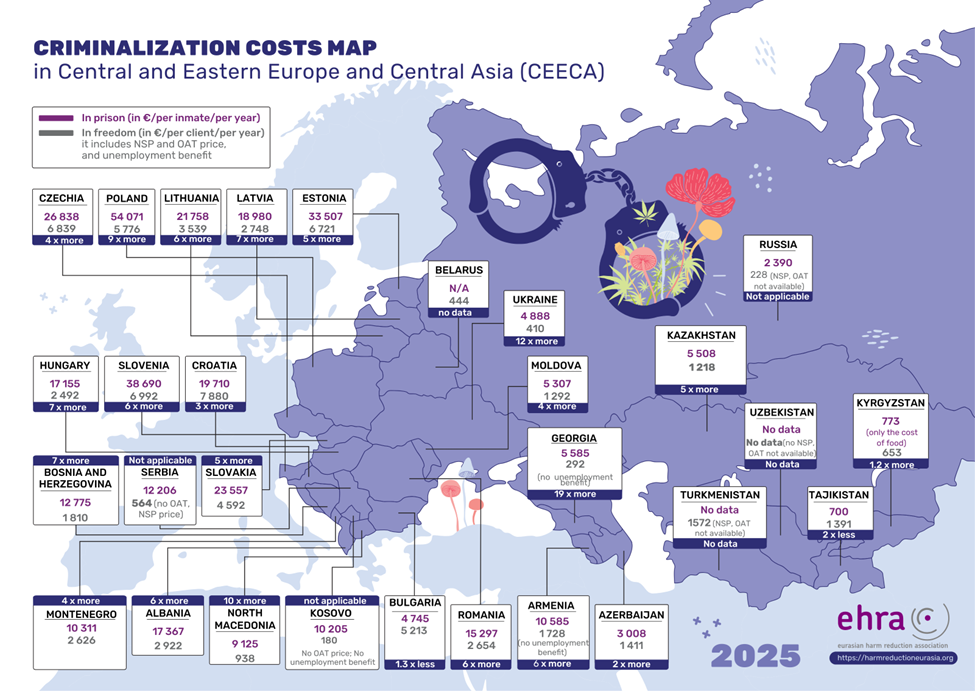

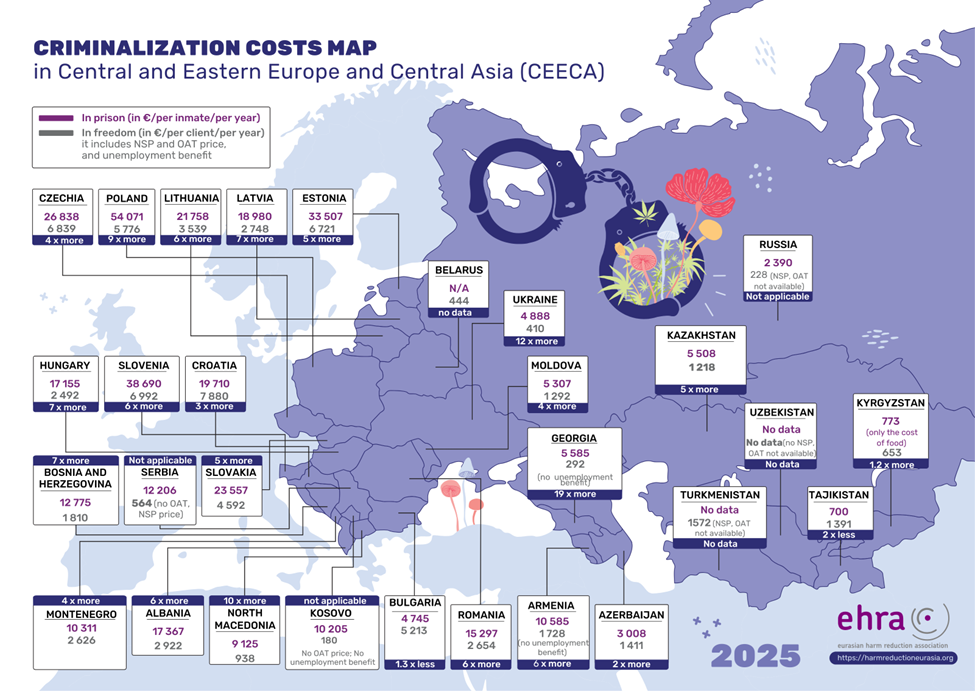

The conversation at the webinar began not with ideology, but with hard accounting. For years, governments in Central and Eastern Europe and Central Asia (CEECA) have claimed they “cannot afford” comprehensive harm reduction services. New data presented by EHRA Executive Director Ganna Dovbakh exposed this as a fiscal lie.

Presenting an updated 2025 comparative analysis of criminalization costs, Dovbakh revealed a staggering gap: in many CEECA countries, imprisoning one person for a drug offense costs the state up to 19 times more than providing that same person with a full package of health and social services (including Opioid Agonist Treatment and harm reduction) in the community.

A full regional comparison and country profiles are available following this link>>>.

But the cost is not merely financial; it is human. To expose this reality, Maria Plotko (EHRA) unveiled “Drug Policy and Economic, Social and Cultural Rights in the CEECA Region” a vital new resource developed by EHRA in partnership with the Helsinki Foundation for Human Rights (HFHR).

But the cost is not merely financial; it is human. To expose this reality, Maria Plotko (EHRA) unveiled “Drug Policy and Economic, Social and Cultural Rights in the CEECA Region” a vital new resource developed by EHRA in partnership with the Helsinki Foundation for Human Rights (HFHR).

Designed to inform the upcoming UN CESCR General Comment, this report acts as a roadmap for civil society, documenting how punitive policies violate rights far beyond the traditional scope of health. The findings-based on consultations across 19 countries reveal a system of “invisible punishment”:

- Right to Work: Administrative fines often lead to total wage garnishment, forcing people out of the formal economy, while rigid OAT schedules and workplace testing prevent stable employment.

- Right to Family: In countries like Uzbekistan and Tajikistan, mandatory testing is required before marriage, and people with a history of drug use are often barred from adopting children.

- Social Security & Housing: “Drug registries” create a catch-22 where individuals are denied state support or housing eligibility based on their status.

The Netherlands: Fixing the “Back Door” Paradox

John-Peter Kools of the Trimbos Institute provided a critical reality check on the famous “Dutch Model.” He clarified that the Netherlands does not have full de jure decriminalisation, but rather a 50-year-old policy of “tolerance.”

While this separation of markets (coffee shops) successfully decriminalised consumption, it left a dangerous legal gap: the supply chain remained illegal (the “back door” problem). This created a paradox where sale is tolerated, but production is criminal, empowering organized crime.

To solve this, Kools highlighted the Netherlands’ bold new step: The Controlled Cannabis Supply Chain Experiment. Currently rolling out in 10 cities, this pilot legalises the entire chain from production to sale. “Decriminalisation of use is not enough,” Kools noted. “Without regulating the supply, you leave the market to criminal networks.” He emphasized that local innovations – cities leading the way – are often the precursors to necessary national reform.

Croatia’s Drug Decriminalization Experience

Sanja Mikulić, from the Institute for Public Health, presented Croatia’s experience with drug decriminalization, noting that possession forpersonal use is treated as a misdemeanor punishable by fine or treatment, with a significant reduction in criminal cases and less pressure on the justice system. She highlighted that th eapproach has led to more flexible procedures, reduced stigma, and easier rehabilitation, while alsosaving budget funds. The presentation concluded with positive effects of decriminalization, including reduced cases in criminal courts and more focus on serious drug-related crimes.

The warning from Portugal: why decriminalization is no longer enough

For two decades, Portugal has been the global poster child for reform. However, Joana Canêdo, a researcher and activist from Lisbon, delivered a critical warning: stagnation is dangerous.

While the 2001 decriminalization model famously reduced HIV rates and overdoses, Canêdo described the current system as a “prohibitionist variant.” The “Dissuasion Commissions,” once hailed as innovative, have become bureaucratic bottlenecks. Approximately 90% of those referred to them are non-problematic users (mostly of cannabis) who do not need treatment yet are subjected to a coercive administrative process.

Crucially, because the market remains illegal and unregulated, the system is struggling to adapt to new trends like crack cocaine. With recent political shifts in Portugal, aggressive policing and stop-and-search tactics have returned. The lesson for the rest of Europe is clear: Decriminalization without legal regulation and continuous investment in services will eventually hit a wall.

The pragmatic revolution: Czechia

However, the most significant innovation is occurring in Czechia. Dr. Jana Michailidu detailed the country’s revolutionary approach to “Psychomodulatory Substances” (such as Kratom and semi-synthetic cannabinoids).

Faced with a surge in new psychoactive substances, Czech politicians initially tried bans. When those bans failed immediately with new chemical analogues appearing weeks later, the government pivoted. They passed legislation creating a strict regulatory market. These substances are not banned, but neither are they unregulated. They are sold only to adults in licensed stores, with strict controls on dosage and packaging.

“We managed to convince conservative politicians that regulation protects children better than bans” Dr. Michailidu explained. By taking the market out of the shadows, the state can control access – something prohibition has never achieved.

In her closing remarks, Ganna Dovbakh dismantled the metric favored by the new EU Strategy: the “kilogram seized.” She termed this the “Kilogram Fallacy.” Seizures are merely an indicator of police activity, not policy success. “You stop one route, ten more appear. You ban one substance; laboratories produce ten new ones. We are fighting a fire with a leaking hose” she argued.

But the cost is not merely financial; it is human. To expose this reality, Maria Plotko (EHRA) unveiled “Drug Policy and Economic, Social and Cultural Rights in the CEECA Region” a vital new resource developed by EHRA in partnership with the Helsinki Foundation for Human Rights (

But the cost is not merely financial; it is human. To expose this reality, Maria Plotko (EHRA) unveiled “Drug Policy and Economic, Social and Cultural Rights in the CEECA Region” a vital new resource developed by EHRA in partnership with the Helsinki Foundation for Human Rights (